[The following essay contains SPOILERS; YOU HAVE BEEN WARNED!]

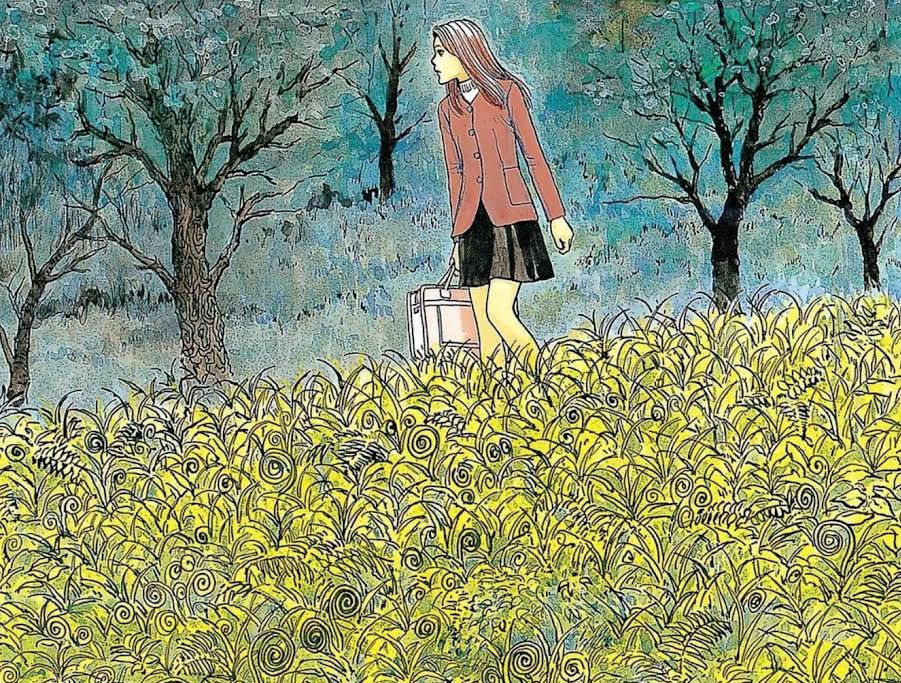

Junji Ito’s Uzumaki begins unassumingly enough. The protagonist, Kirie Goshima, meets her boyfriend, Shuichi Saito, at the local train station. He’s in a foul, broody mood; ever since he started commuting to a school in a neighboring prefecture, he can’t help but notice the oppressively gloomy, dismal atmosphere that pervades their sleepy hometown of Kurouzu-cho: the thick, dreary clouds blanketing the sky; the crumbling, dilapidated row houses wedged in between newer apartment buildings; the ominous abandoned lighthouse looming just off the jagged, rocky coast. He insists that something that he can neither articulate nor explain is fundamentally wrong with the community, and that they must flee lest they, too, are consumed by its corruptive influence. But despite witnessing innumerable atrocities that would drive any rational person to the brink of insanity, our heroes continually fail to actually leave (even before the roads, tunnels, and alleyways twist themselves into a literal labyrinth); it’s as though an invisible tether inexorably draws them back—like marbles rolling down into a hole at the bottom of a steep incline.

“Uzumaki” is the Japanese word for “whirlpool,” though it is also used more broadly to describe spiral shapes in general. In Ito’s hands, the image of a swirling, spinning pattern becomes a versatile metaphor, symbolizing everything from obsession to paranoia to infatuation to vanity. Occasionally, it doesn’t “mean” anything concrete, appearing only as a vague signifier of the presence of the paranormal. Indeed, the episodic (albeit interconnected) stories become increasingly supernatural as the series progresses; the characters are terrorized by, among many other nightmarish monstrosities: sentient hair that demands adulation, pregnant women that crave blood following encounters with swarms of unusually aggressive mosquitos, and abnormally intelligent infants that long to return to the comfort of the womb.

While the comic’s genre gradually veers towards apocalyptic/survival horror, however, its central themes remain inextricably interwoven with the comparatively mundane anxieties established in the initial chapters. Kirie and her family are firmly rooted in place, immobile as stone statues, unable to escape the soil upon which they were born; in the aftermath of multiple devastating hurricanes, for example, standing in the middle of a street strewn with rubble and corpses, her father makes it abundantly clear that he intends to stay put and rebuild his modest pottery business—an utterly absurd proposition, considering the irreparable destruction surrounding him.

And his all too recognizable, relatable attitude—that foolish rejection of reality, that refusal to alter one’s own self-destructive behavior, that delusional belief that everything will simply “work out” in the end—is significantly more unnerving than humanoid snails, spring-heeled zombies, and ancient curses.

Comments